The word “pill box” (or pillbox, pill-box) is often today defined as a structure which gets its name from a resemblance to a tablet or medicine container. This etymology is often perceived as being historically factual, and has found its way into an oft-quoted dictionary, Brophy and Partridges dictionary editions of WW1 slang, which will be addressed in the text below, and even the modern on-line Wikipedia. However, it has been found that this presumption is unlikely to be correct and the origins of the word have little to do with medicinal storage.

Several claims have also been made that the word first appeared in The Scotsman, 17th September 1917: however it had already appeared in print, on the front page of The Times August 2nd 1917, immediately following the beginning of Third Ypres, which became better known as Passchendaele. Describing the attack which launched the Third Battle of Ypres, 2 days earlier, the war reporter wrote:

“The favourite type of German stronghold is a structure of concrete made all in one piece, and not built of blocks, which has been named “the German pill box”. Used singly they are merely shelters or substitutes for dugouts. With the proper internal arrangements and loopholes they are machine-gun posts, or clustered together they make redoubts. They are not easily destroyed by shell-fire, but so terrific was our bombardment of the area attacked that these pill-boxes, where they were not shattered, were thrown upon their sides or left ridiculously standing on their roofs. Some are big enough to hold 20-30 men”.

It has also been written that the British first encountered these structures during the Battle of Third Ypres, which is incorrect. The British began making concrete machine gun posts in 1915 (as recorded by 7th, 57th, 70th, 509th, Field Companies R.E. and others), as did the Germans. There are numerous records of “concrete machine gun emplacements” and shelters being constructed in 1916 R.E. War Diaries. It has been stated that the name arose because of the circular shape. However, between 1915, when both sides began making shelters of bullet and shell-proof concrete, and 1917, there were very few circular concrete machine gun posts. The vast majority were square or rectangular in plan. The British produced some circular pill boxes later, in the summer of 1918: the Moir Pill Box, a 6ft diameter, 2 man (gunner and loader) emplacement which was pre-cast in Richborough, Kent, and some formed of pre-cast blocks on the East Anglia coast. The Australian Engineers also designed and built, near Messines, an observation post formed within up-ended elephant-iron sections. The Germans, later in the war, also produced some standard designs and patterns for structures, with standard fittings, all of square or rectangular shape. In practice it is very difficult to produce a circular concrete shape without special formwork. Those built in the field, in both forward and rear positions, by both Germans and British utilised materials to hand, most commonly wooden boards and planks, sheet corrugated iron, wood fascines, existing and broken masonry and available building materials.

An existing example of an early (1916) British concrete construction, (observation post) at Le Rutoire, France, shows how it was cast against corrugated iron sheeting.

Some typical examples of those being constructed by the Germans around Ypres in late 1916/early 1917. The methods of formwork, giving the shape (rarely or never circular), and camouflage can be seen. These constructions proved considerable obstacles during the fighting in 1917.

A number of examples of the above constructions still exist in the Ypres area, nowadays generally devoid of the formwork and camouflage. A particularly famous one, in Tyne Cot Cemetery near Passchendaele, Belgium, is shown. The name is often stated to have been given by Northumberland Fusiliers to cottages, which reminded them of similar cottages at home, which stood here; however other suggested origins are the Tyne river (Marne, Seine and Thames Farms are nearby) and the anglicisation of the ’t Hinnekot (chicken coop) belonging to the Heveraet/Debruyne families who farmed here up to the start of the fighting. This pill box and 2 adjacent ones proved considerable fortifications against the British and Australians, who captured them after very heavy fighting, with many losses.

Shell-proof cover was often produced, by both sides, by laying concrete over curved elephant –iron cupolas, although the floor plan was rectangular.

Existing typical British shelter in Belgium, comprising concrete poured over “elephant-iron” cupola. The Germans used a similar pattern.

The British started constructing “concrete machine gun emplacements” in 1915, 2 years before the term “pill box” appeared in print, as did the Germans. There are numerous records of “concrete machine gun emplacements” and shelters being constructed in 1916 R.E. War Diaries. Many RE Field Companies and infantry units, providing working parties, had experience of constructing these structures, as there was much labour involved in excavating footings, carrying materials, mixing and placing concrete. RE, machine gun battalion and Divisional records almost always refer to “concrete machine gun emplacements” or “concrete dugouts”. It is unlikely that any Tommy would say that he was working on a “concrete machine gun emplacement” and it is likely that a slang term was adopted fairly early on. However, few officers, in writing the daily War Diary, used the slang terms spoken by troops.

The first written description – “Pillar Box” appears in the war diary of 63rd Field Company R.E., 9th (Scottish) Division, who recorded in their work schedule of observation and machine gun posts and around Ploegsteert Wood and Hill 63 in March 1916.

Over the late summer of 1917 the term pill box became widely accepted and began to appear in war diaries and other documents. By October the term was widely used. The Intelligence Summary of 1st Anzac Corps, dated 5th September 1917, planning for the forthcoming taking over of the front lines and subsequent attacks on the German trenches and “pillar boxes” at Ypres by the Australians described the obstacles expected. This was recorded in the Official History of Australia in the War 1914-18 (Bean)(1).

The term “pillar box”, and the form “pillbox”, are given in the British Official History of the War (Edmonds)(2) describing the Battle of Messines Ridge in June 1917.

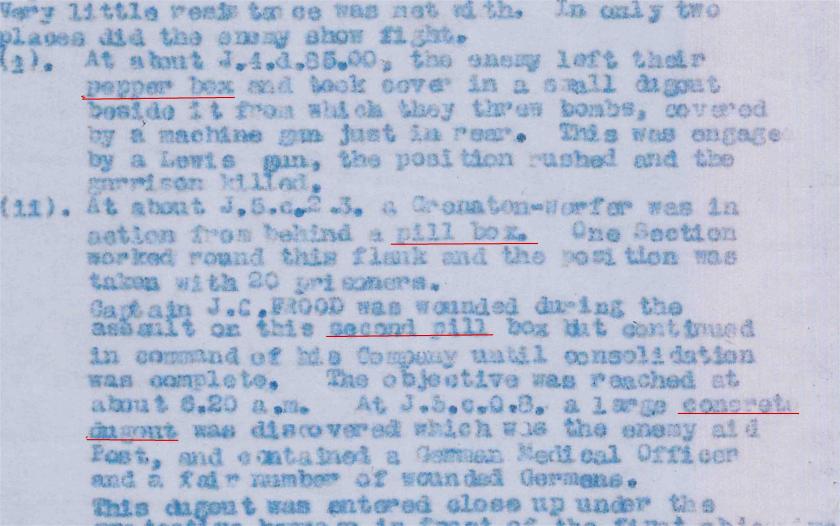

Other terms were also coined, such as the 8th Devons using both “pepper box” and “pill box” interchangeably. A report for the daily war diary, written the day following the events, on an attack on the German lines by this battalion at the opening of the Battle of Broodseinde, a forerunner of the battle of Passchendaele, contains many references to pepper boxes, pill boxes, and concrete dugouts as in the extract example below (underlined in red as original typing indistinct):

“Blockhouse”, from the Boer war, and “concrete dugout” were frequently used in daily war diaries until the slang “pill box” became more officially accepted and used in records and plans. “MG nest” was also used in some instances by the Canadians, and later the Americans, although not widely adopted by the British. “Concrete fort” was also used, generally in descriptions of German defences. A search of usage within war diaries and contemporary official documents shows the wording had three presentations: ‘pill box’, ‘pillbox’ and ‘pill-box’. Of the 3, the first, ‘pill box’ was most commonly used to describe both British and German constructions, in much greater numbers than the other 2, probably about sixty per cent of the time.

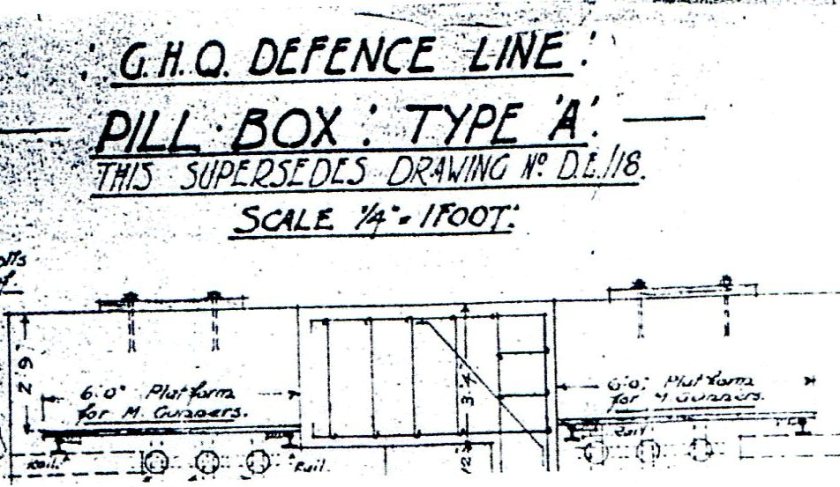

A pre-cast block and beam system was developed:

Poured or in-situ concrete patterns were also produced:

The Royal Engineers who designed and constructed the various emplacements preferred the term ‘pill box’. ‘Pillbox’ and ‘pill-box’ were also used, and ‘pillbox’ as one word has increased in usage and is nowadays probably the most commonly used. The author has however maintained the use of ‘pill box’ when writing, as being more historically correct.

Of the many concrete constructions built in France and Belgium by both sides during the First World War, only a small proportion were intended as to be used by machine gunners. Most did not have loopholes or apertures for firing from within. The majority were simply to be used as shelter from artillery and aerial bombardment for unit headquarters, aid posts, artillery command posts, observation posts, and engineer protection etc. Many would be known today as a ‘bunker’, although this term was not used 1914-18, and they were generally known as ‘dugouts’ even when above ground. The vast majority were of poured and cast in-situ concrete, against whatever shuttering could be supplied or found, with the Germans producing a small number of pre-cast block structures in 1917, and the British producing pre-cast block and beam patterns in 1918. With the exception of the Moir Pill Box, all were square or rectangular.

Circular Pill Boxes

Circular pill boxes were quite rare. This is because constructing a round shape in concrete, especially when reinforced with iron, is quite difficult, especially in battlefield conditions, and needs special formwork. The advent of pre-casting, in factories behind the lines, did make this possible.

The French had a number of circular protective posts made of cast steel, adopted from earlier border forts, but these were few in number due to transport practicalities. The Germans produced machine gun emplacements and shelters utilising pre-cast blocks in 1917, but their designs were all square or rectangular, comprising 4 walls of concrete blocks and a roof cast in place. The British adopted this idea, improving the system to use both blocks and beams, as in Figures 14 and 15.

The only circular pill box in usage on the western front was that designed by Sir Ernest Moir: interlocking circular segmented concrete blocks, cast at Richborough, Kent, with a metal cupola, sent out to France and Belgium in kit form in the summer of 1918.

With the increased threat of a German invasion after the winter of 1917/1918 (which became the Spring Offensive, Operation Michael, launched against the British, beginning 21st March 1918, when the Germans almost pushed the British army back to the channel ports) the coastal defences in eastern England were greatly strengthened. A series of circular pattern emplacements comprising pre-cast concrete blocks was constructed by Royal Engineers, of 64th Division, Home Defence Force, in spring and summer 1918 to produce machine gun/rifle posts and a number of these, at least 12, can still be found on the East Anglian coast today.

It has been claimed(3) that these structures are the origin of the name pill box, but by the time of their construction the term had been in use in France and Belgium for two years. When the 1940s coastal defences were constructed, with the renewed threat of German invasion, again most structures were not circular in plan, but rectangular or hexagonal, because of the normal casting of concrete against formwork. By now the name pill box was synonymous with fixed defences.

Probably the first dictionary definition is given in Weekley’s Etymological Dictionary of Modern English in 1921(4):

“Pill-box, small concrete fort, occurs repeatedly in offic. Account of awards of V.C. Nov 27, 1917.”

Subsequent post-1918 dictionaries of soldier’s slang such as Fraser and Gibbons’ Soldier and Sailor Words and Phrases (5) (1925) and Brophy and Partridge’s Songs and Slang of the British Soldier (6) (1930) do not support the description of a tablet container. Fraser and Gibbons give the following:

PILL BOX-: The name, from the shape (often circular) in plan and roughly suggesting a ship’s conning tower) for the German ferro-concrete small battle-field redoubts or forts, employed from the autumn of 1917 onwards to defend sections of the line in Flanders. Some of the larger were quadrilateral in shape. They were garrisoned by small detachments of infantry with machine guns and were proof against anything except a direct hit by a big gun. The capture was often effected by infantry with hand grenades flung into the entrance at the rear or through the loopholes while other infantry kept down German rifle fire by shooting at the loopholes.

Although the shape described (“often circular”) and the chronological origin (“autumn of 1917”) can be debated, there is no reference to medicinal containers.

Brophy and Partridge, in their original 1930 edition, give:

A small fortification of reinforced concrete used especially for machine guns. A German invention.

Again, no mention of shape. However a later (1965) edition, with a changed title(7) enlarges on this and perpetuates the description of the shape: the above definition plus a second sentence:

The English name is from the cylindrical shape.

This later edition also refers to ‘Moir’s Pill-Box’, “a cylinder shaped machine-gun turret” and gives a technical description of this pattern of factory pre-cast machine gun emplacement manufactured in England in summer 1918. (See Figure 18 above for an existing example of this pattern). It also states that these pill boxes were used during the Second World War:

They became much better known during the 1939-45 (Hitler) War.

The author has found no evidence that the Moir Pill Boxes erected in 1918 in France and Belgium were used 1939-45 on what was the Western Front, although it is known that the British, in 1940, did use First World War defences when being pushed back, eg Hill 60 south of Ypres.

Note: As a result of this research and correspondence with the editors of the Oxford Dictionary, the Oxford Online Dictionary has amended its definition of pill box from originating with the Germans in 1917 to the following:

Mil. A small concrete fortification used as a gun emplacement, observation point, etc. The first pillboxes were built by the British and German armies in 1915, during the First World War (1914–18).

It is expected that at some time in the future, when re-edited, the printed Oxford English Dictionary will carry similar wording.

References

- Official History of Australia in the War 1914-1918. Vol iv 1917. CEW Bean.

- Official History of the War. Military Operations,1917, vol II. Sir JE Edmonds.

- Journal of the Norfolk Industrial Archaeology Society. Vol 5, No 1, 1991.

- An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. Ernest Weekley. 1921.

- Soldier and Sailor Words and Phrases. Fraser and Gibbons, 1925.

- Songs and Slang of the British Soldier. Brophy and Partridge. 1930

- The Long Trail: Soldier’s Songs and Slang 1914-1918. Brophy and Partridge 1965.

Peter Oldham is a (retired) concrete technologist with over 40 years experience of concrete construction materials and methods. A Fellow of the Institute of Concrete Technology, he has studied WW1 constructions for many years. Books written include Pill Boxes on the Western Front and Armageddon’s Walls: British Pill Boxes and Bunkers, 1914-1918, as well as battlefield guides (“Messines Ridge” and “The Hindenburg Line”). A recent paper in the Institution of Civil Engineers “Magazine of Concrete Research” was entitled “From Extemporised to Engineered. Developments in Concrete Technology During the First World War”.

Our first thought, from the point of view of language change, is – why did it change from ‘pillar-box’ to ‘pillbox’? After all, it is easier to say ‘pillar-box’ than ‘pillbox’; the rhythm helps a faster enunciation, despite the increased number of syllables. Perhaps the answer lies in the distance between the associations – the gun emplacements were, from the point of view of most British and Anglophone soldiers, negative. These were things to be associated with death, wounding, the odds in favour of the enemy, failure. Pillar-boxes, however, carried associations of home, and even more, contact with home. Pillar-boxes meant news from home, home comforts, news of loved ones, cigarettes, newspapers, good things. Perhaps these associations were too far apart.

But, soldiers named enemy shells and weapons after foods that they longed for – sausages particularly (though sausages were at this time strongly associated with German culture), especially in the phrase ‘Zepps in a cloud’ (sausage and mashed potatoes). Sometimes there appeared to be a kind of tacit policy of not causing friction in the use of slang and colloquial terms – we think particularly here of the phenomenon of the thousands of trench names that were used, and the troops’ obsession with football; yet when the two are put together, there were only two instances of naming trenches after football grounds. An internal truce.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. There are something like 25 WW1 pill boxes extant in Norfolk, 3 are Hexagon and constructed by using shuttering and poured concrete.

LikeLike