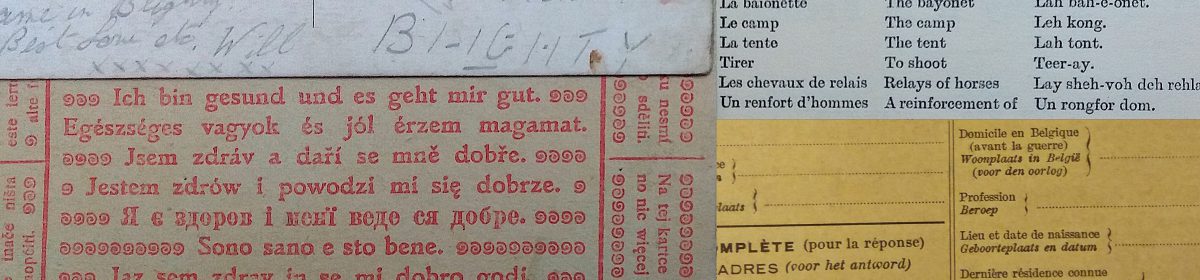

It would be good to know what Lucien thought of the slang as presented in the image. He uses the slang word ‘copains’, which Dèchelette defines as ‘camarade[s]’, coming from the old word ‘compain’ (compagnon). Leroy translates it as ‘friend, pal, chum’.

Comparative commentary on the vocabulary shows how variable slang can be. Partridge in Words! Words! Words! (1933) has an extensive essay on the slang of the French soldier, which in place of bricheton has ‘Briffeton, perhaps related to the Poilu briffer, to eat, … much less used than brigeton.’ Leroy gives both of these, with briffer and brichetonner, to feed; Dauzat also, but without brichetonner; Dèchelette has only bricheton. Sainéan gives Bricheton, pain. Mot de caserne tire des patois: c’est le diminutive du normand, brichet, pain d’une ou deux livres, de forms variées, qu’on fait expressément pour les bergers.

Probably all of the words shown would produce rich etymologies; those that stand out for us are godasses and singe. For Sainéan godasse and grolle are both ‘soulier’, grolle being a ‘provincialisme’ and godasse a ‘soulier large … semblable à un godet (bucket)’. Leroy points out that ‘godasse’ was a ‘popular pronunciation of gothas, German aeroplanes’. Dauzat and Dèchelette give ‘soulier’, Dèchelette adding ‘Ce mot a complètement détrôné les anciens vocables; croquenots, godillots, pompes, tatannes. Le soldat est rarement satisfait de ses godasses, mais il marche quand même.’ Dauzat has ‘grole’ rather than ‘grolle’ (Dèchelette, Leroy, Sainéan).

It is not surprising that tinned meat, being of major importance to front-line soldiers, should have a strong slang identity, nor that there should be a range of etymologies: Partridge proposes an origin from the French military experience in Africa:

For Dèchelette there is the possibility of a commercial origin:

And Dauzat notes the development from singe to gorille, a good example of how slang grows.

Sainéan, describing singe as ‘Mot de caserne’ (barracks), quotes a French trench journal article, a mock ethnographic report on ‘Une France Inconnue’, in which Becquetance (‘food, grub’, Leroy) is described as ‘brouet (brew) don’t la composition varie par l’alternance de ces deux éléments : Ex., le matin, riz et singe; le soir, singe et riz,’ showing that the French soldier’s sense of irony was easily as developed as the British soldier’s.

Lazare Sainéan, L’Argot des Tranchées (1915)

Albert Dauzat, L’Argot de la Guerre (1917)

Francois Dèchelette, L’Argot des Polius (1918)

Oliver Leroy, A Glossary of French Slang (1922)

Eric Partridge, Words! Words! Words! (1933)