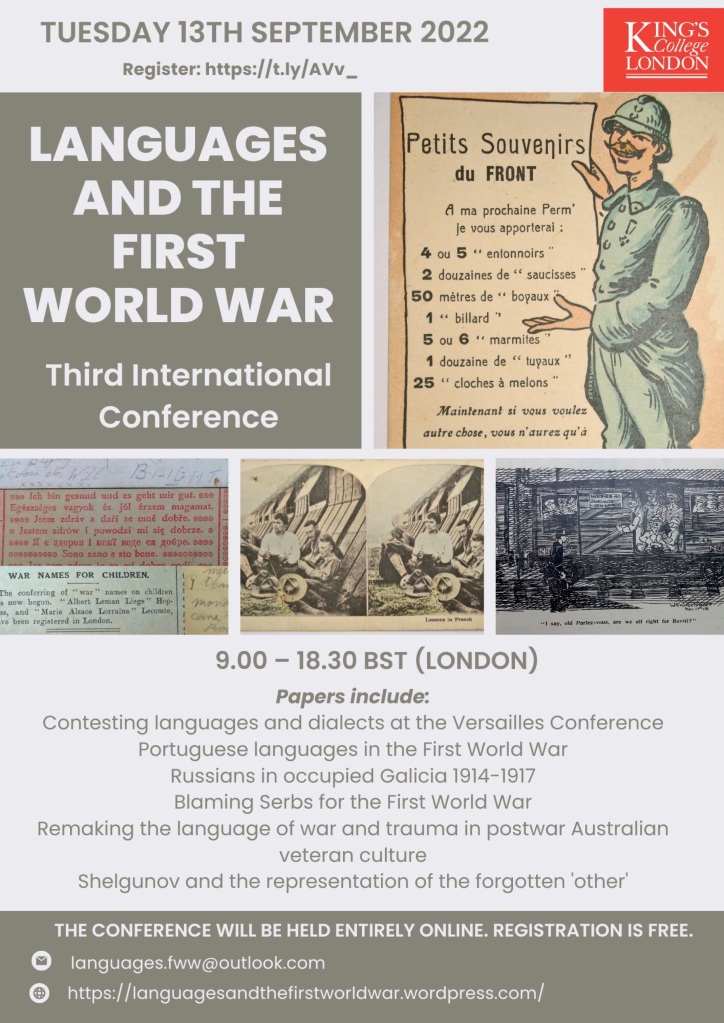

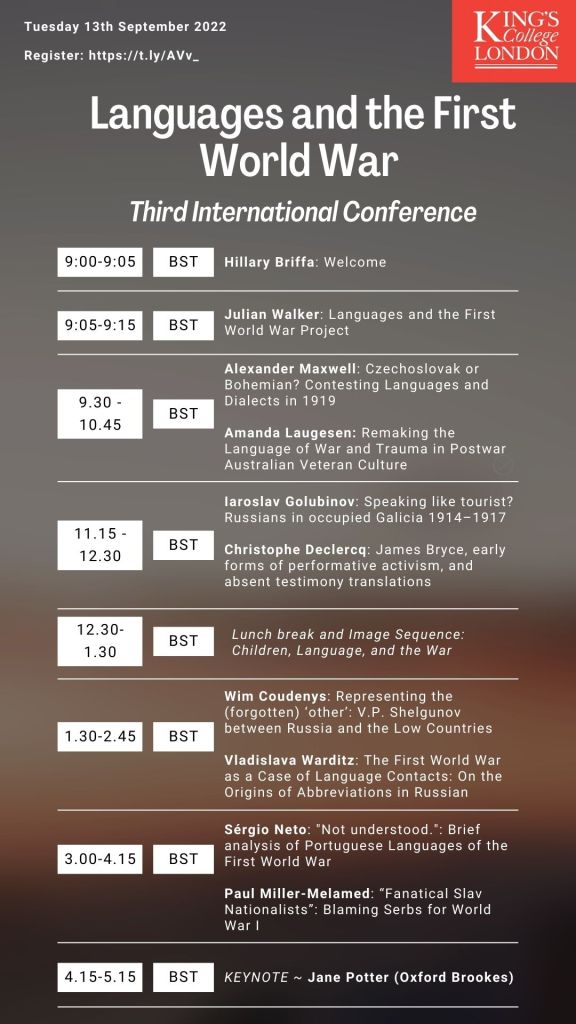

Many thanks to all who contributed to the third conference conference (13th September 2022), from several different time zones (which meant the conference actually stretched over two dates). It was great to have material on the Portuguese linguistic reaction to the war, and more focus on the Eastern Front and the Russian experience, while revisiting the rich themes of evidence, propaganda, phrasebooks, and the post-war linguistic experience that were a feature of our previous conferences in 2014 and 2018.

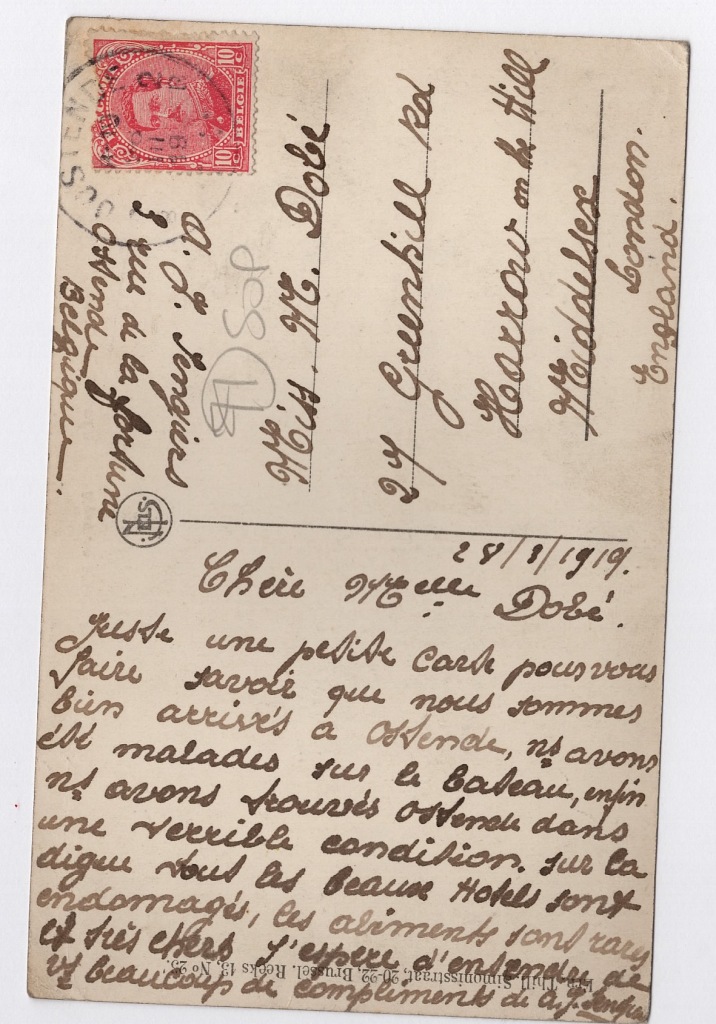

Themes that emerged linked with previous papers and research, adding to the depth and breadth of investigations into how the war changed language, and how language changed the way people have looked at the war, from the Armistice to the present. The relationship between the spoken and the unsaid, so important an aspect of the two reports published under the aegis of James Bryce (presented by Christophe Declercq), may be considered alongside the development of war language in post-war Australia (Amanda Laugesen), and how the war was reported between nations and languages (Wim Coudenys).

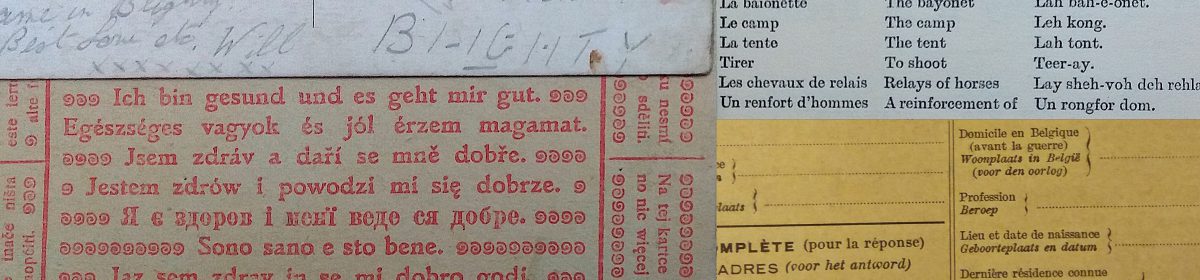

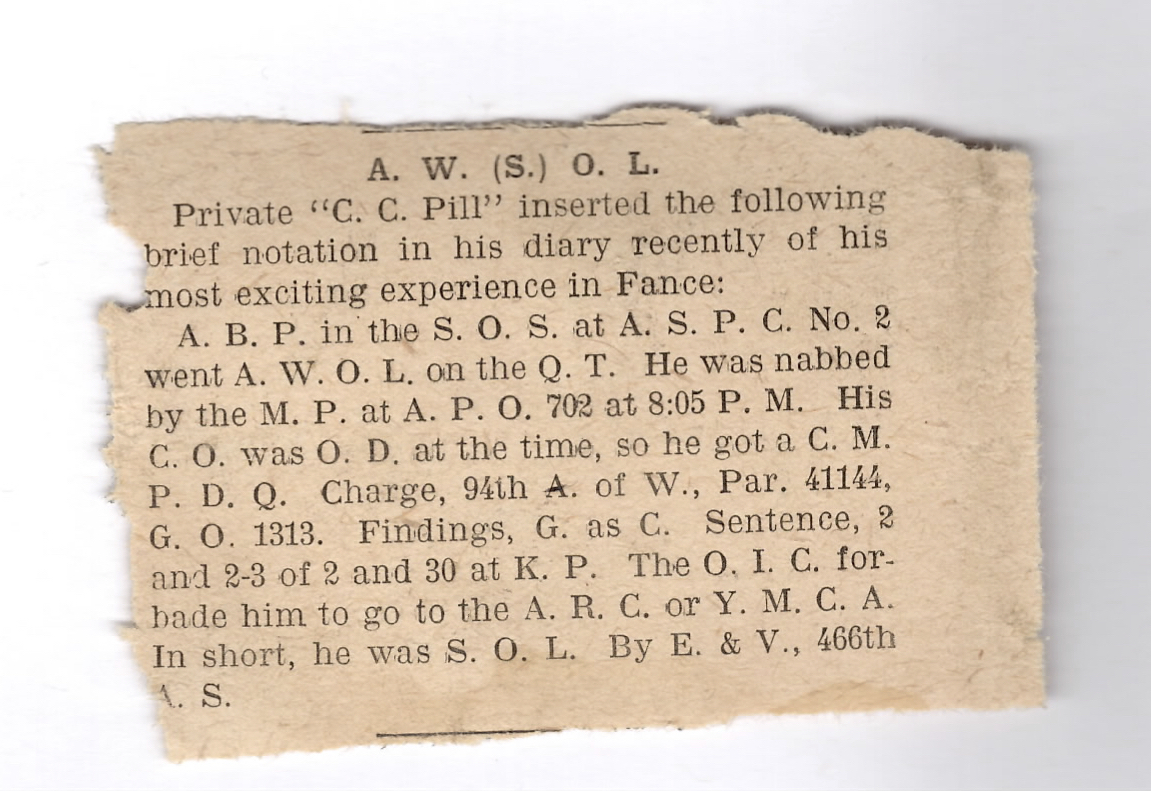

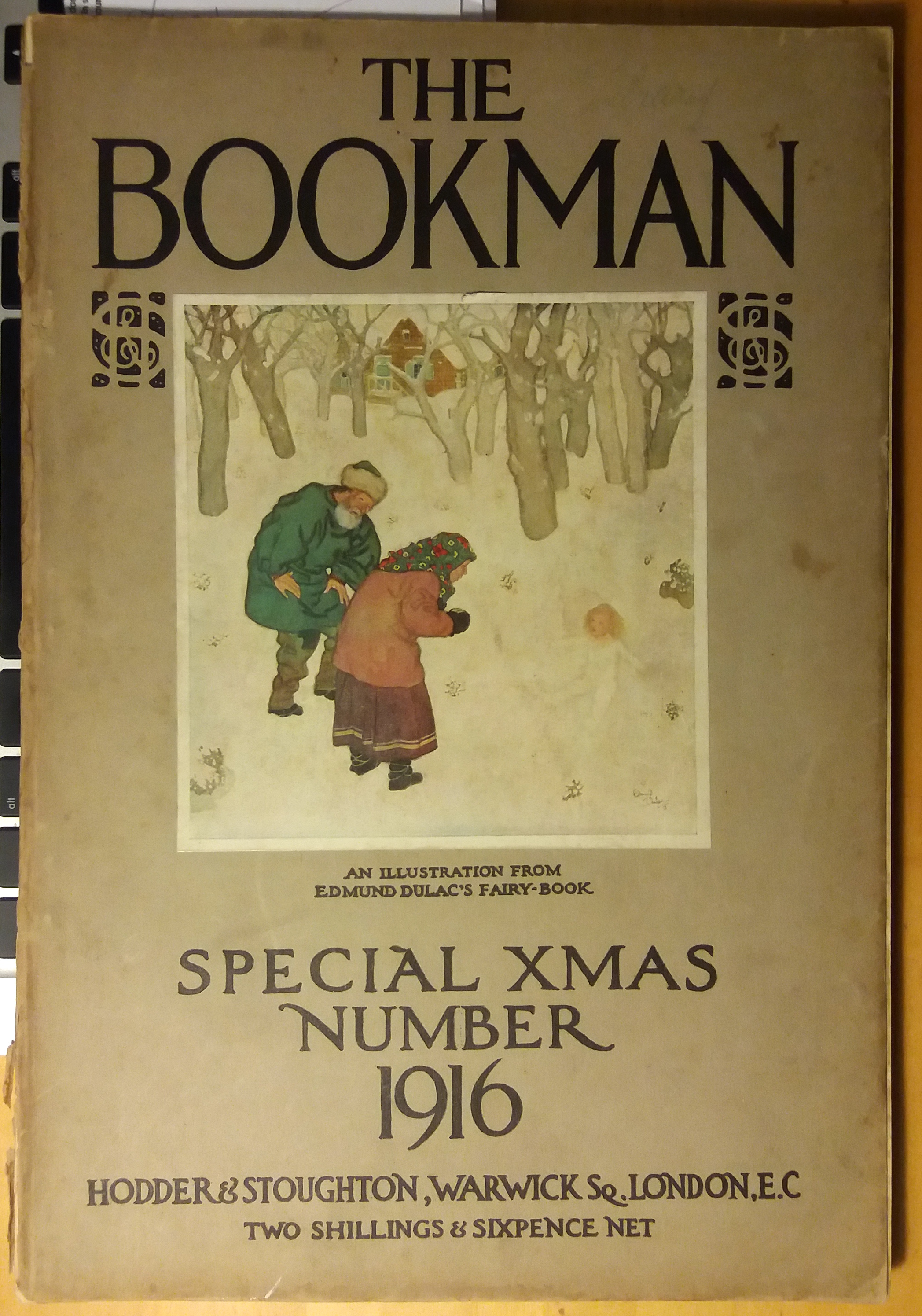

The searching for ways to express the experience of the foreign, especially where models of tourism offered paths for communication – or where the lack of models gave space for basic metaphors of food – were the subject of papers by Iaroslav Golubinov and Sérgio Neto, while Vladislava Warditz’s presentation on the emergence of abbreviations and acronyms in wartime Russia links to the range of methods of communication, as well as their concise power as tools for propaganda. The boundaries of the basic question of what constitutes a language were as political as they have always been (the subject of Alexander Maxwell’s paper), but perhaps more so during the period before, during and after the Great War, as the boundaries of nation-state, province, region and identity were wrenched one way and the other. The question of ownership of language has been a constant theme in this project; the identities of states and countries have been confused in the continued storytelling of the assassination in Sarajevo – Paul Miller-Melamed’s paper showed how the name of the ‘nation’ under which this was carried out has been less than fixed, a product of propaganda, misinformation, laziness and rumour. The mythologizing of war, while it was happening, as non-official propaganda ranged from ‘soft’ messages shown on the cover of popular novels to the now canonical view of the experience of war in Wilfred Owen’s poetry, as revealed by the subject of Jane Potter’s keynote paper. This keynote brought together many ideas: – the nature of the power of iconic terms such as ‘the pity of war’, the power of selected words to put other words so far into the background that they become silences –, equally eloquent in themselves as the withholding of speech becomes a testament itself; and the way we are still searching for ways to talk about this extraordinary story.

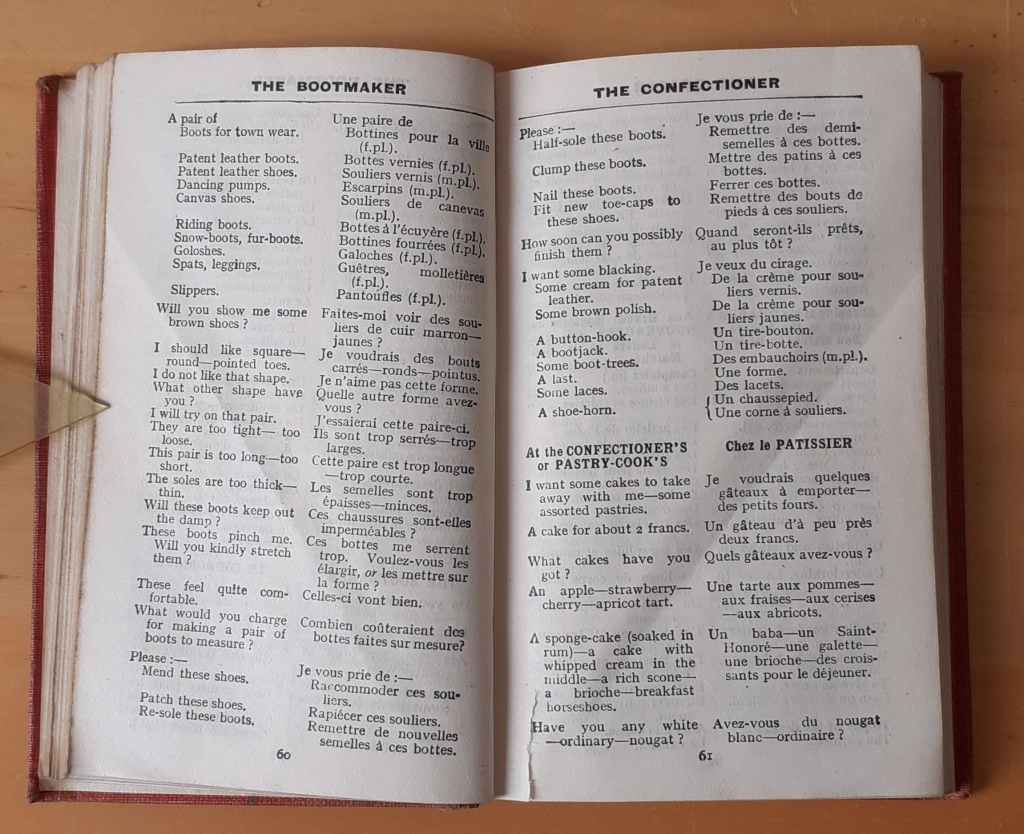

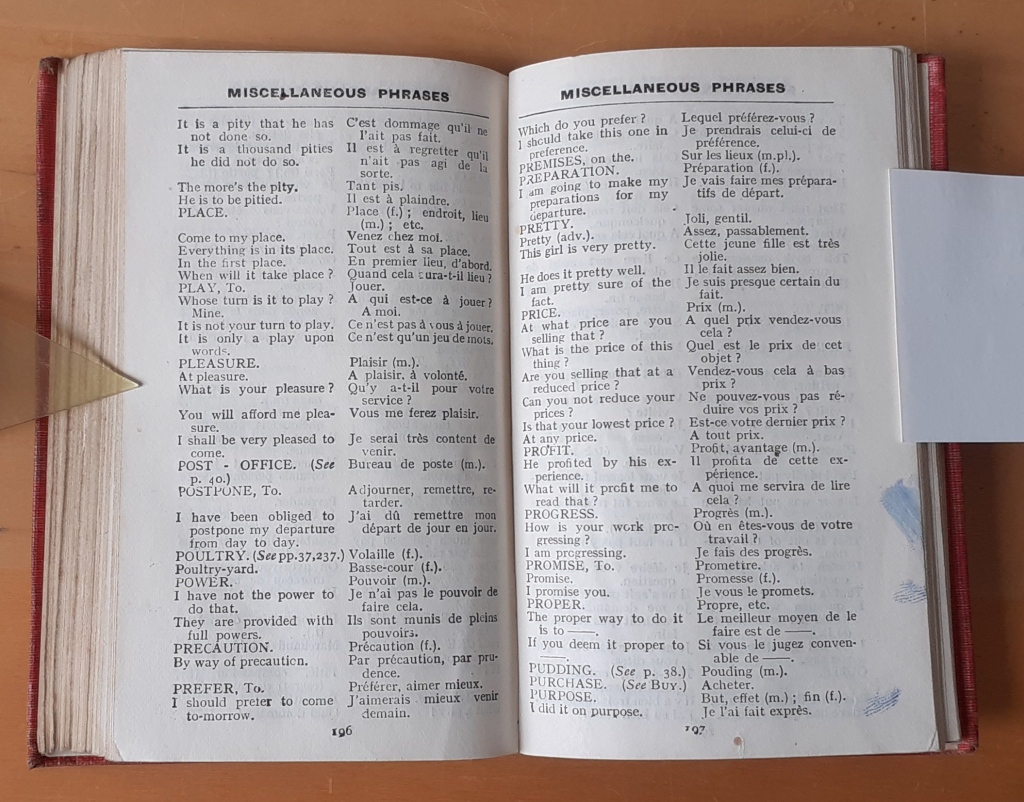

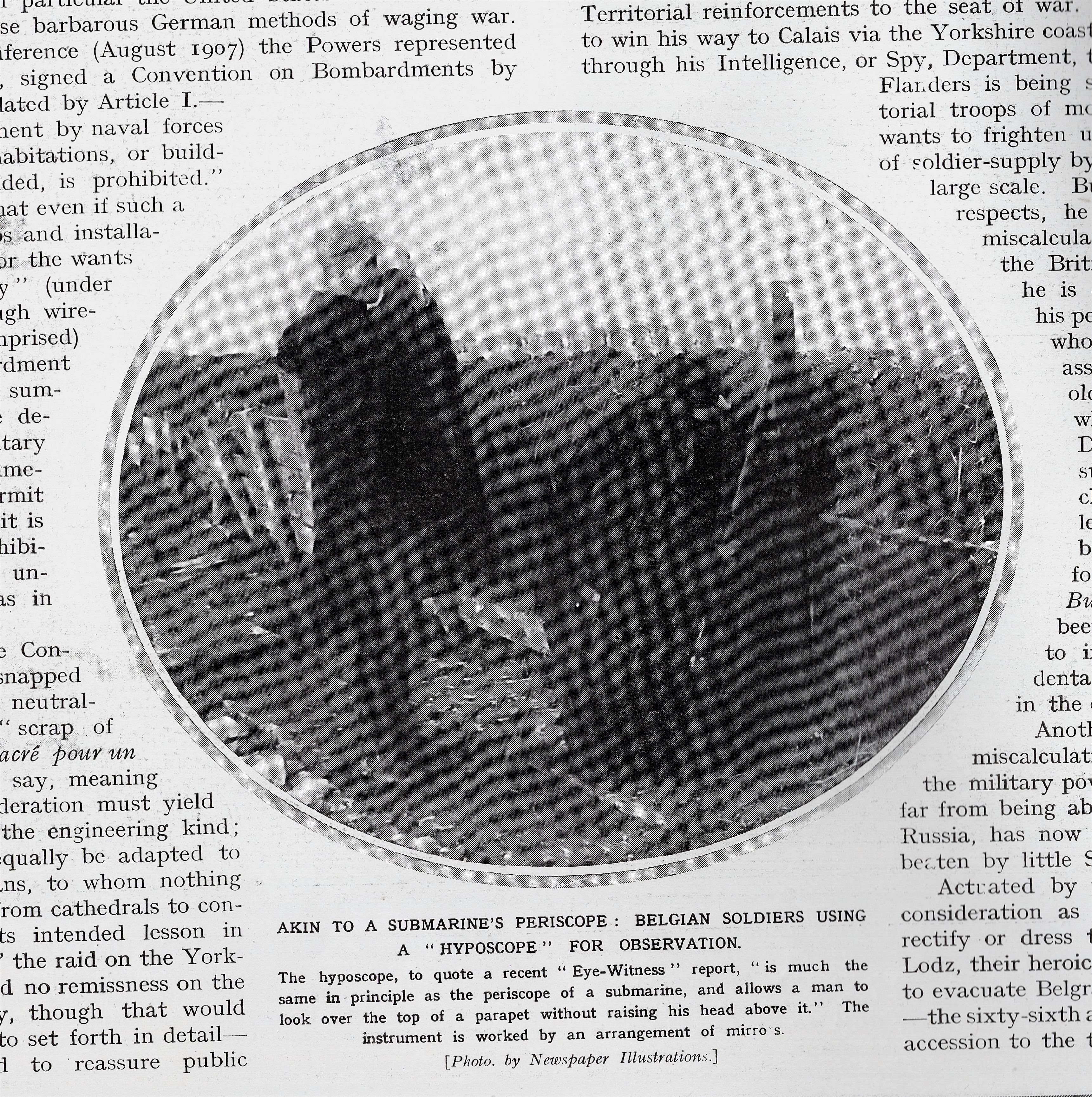

Prompted by Paul Miller-Melamud’s paper on the mythologising of the Sarajevo assassination, this item was posted in yesterday’s conference, referencing the propaganda that started immediately on the outbreak of war, and the theme of food, which has characterised much of the research presented at the conferences, including the similarities between English and German food metaphors (Peter Doyle, 2014), food queue slang in Russia (Iaroslav Golubinov, 2018), and Portuguese trench slang (Sérgio Neto, 2022). Note here the spelling of Serbia, which was changed from ‘Servia’ around September 1914. The value of the conferences has been the opening up of areas, and sometimes extremely focused subjects, which challenge us to look at sometimes startling differences, as well as similarities across time and space, while providing comparisons between developments.

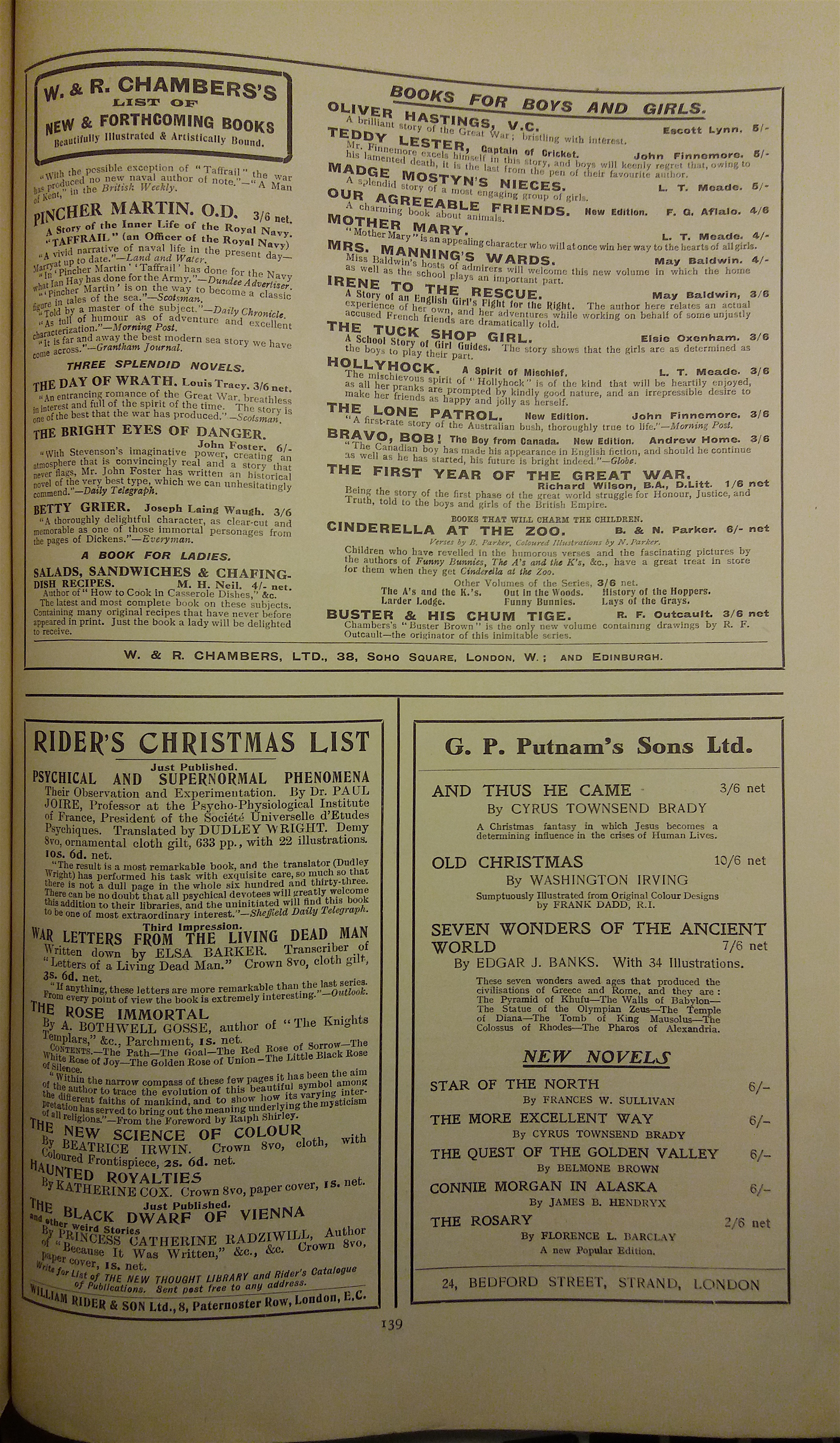

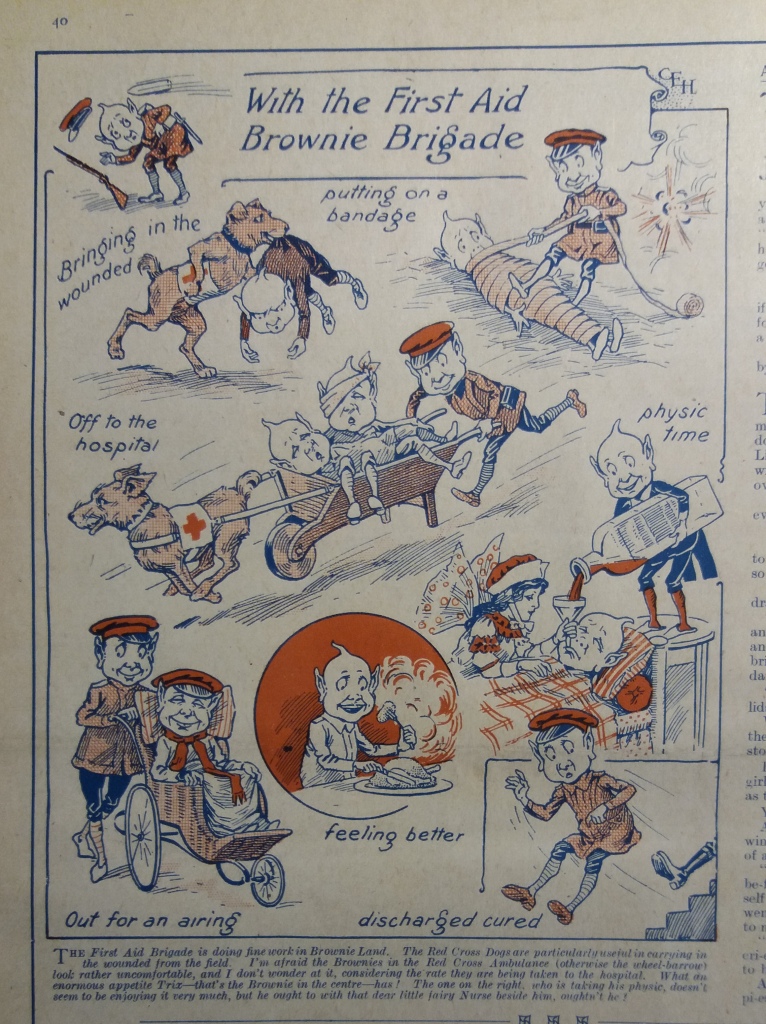

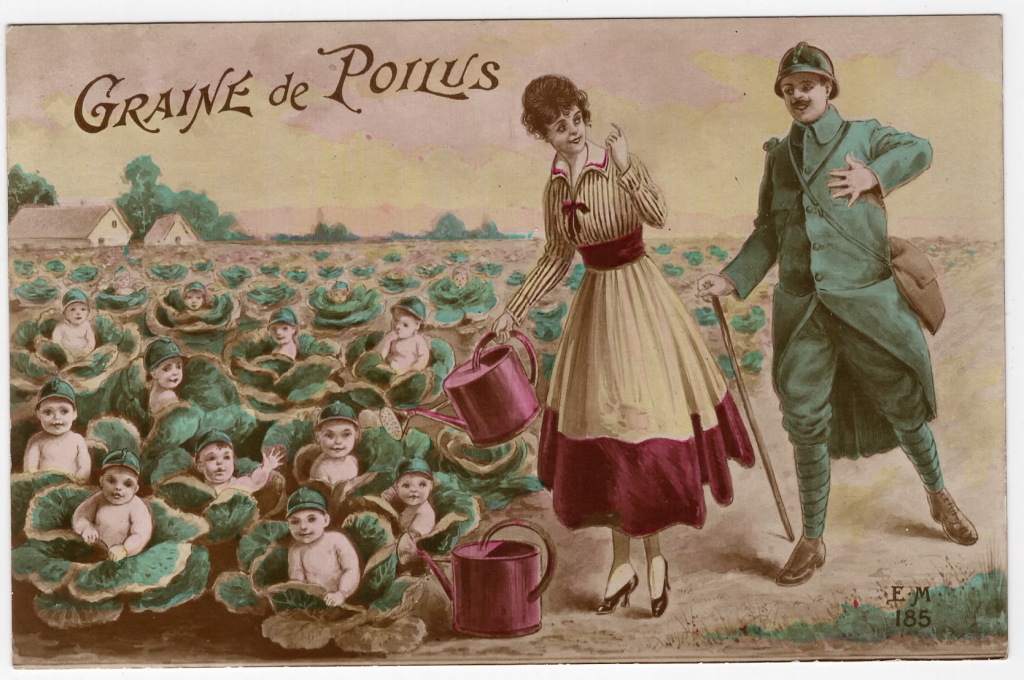

Also shown are a few images from the lunchtime presentation of how children were brought into the language of the war. The subject areas introduced here include the pictorial infantilisation of the war, the normalisation of war for very young children, the portrayal to children of children playing war, and how some books directed at infants introduced war terms, such as ‘souvenir’ and ‘Hun’ to very young children. The sequence ended with the naming of babies after battles, and the putting into the mouth of a young child the question ‘Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?’

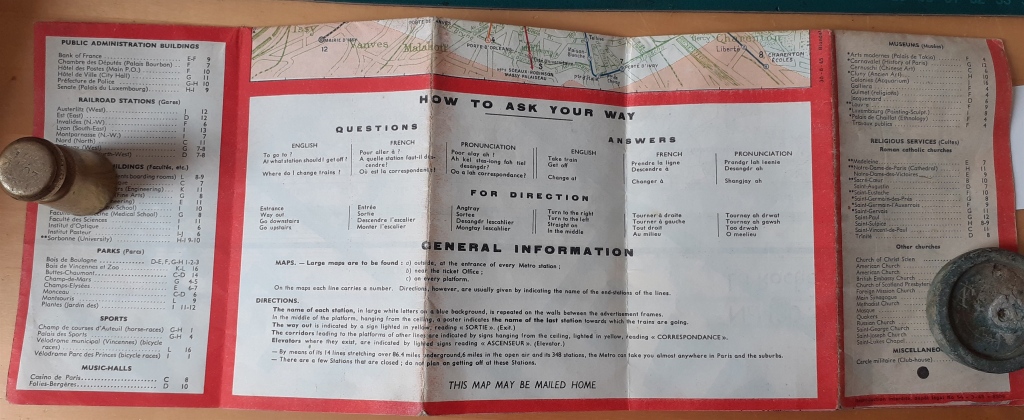

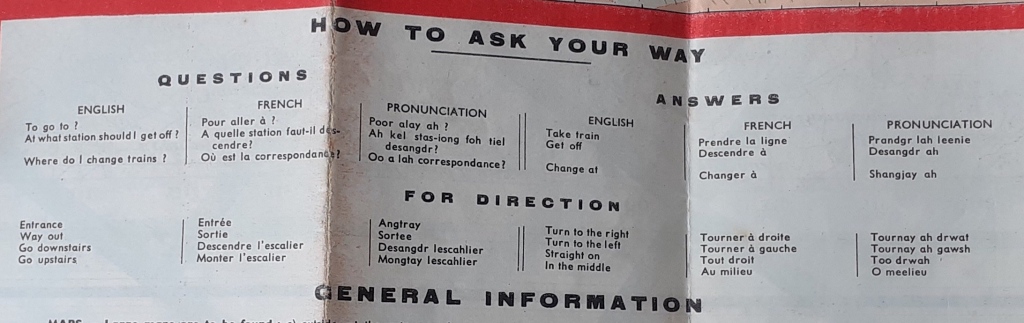

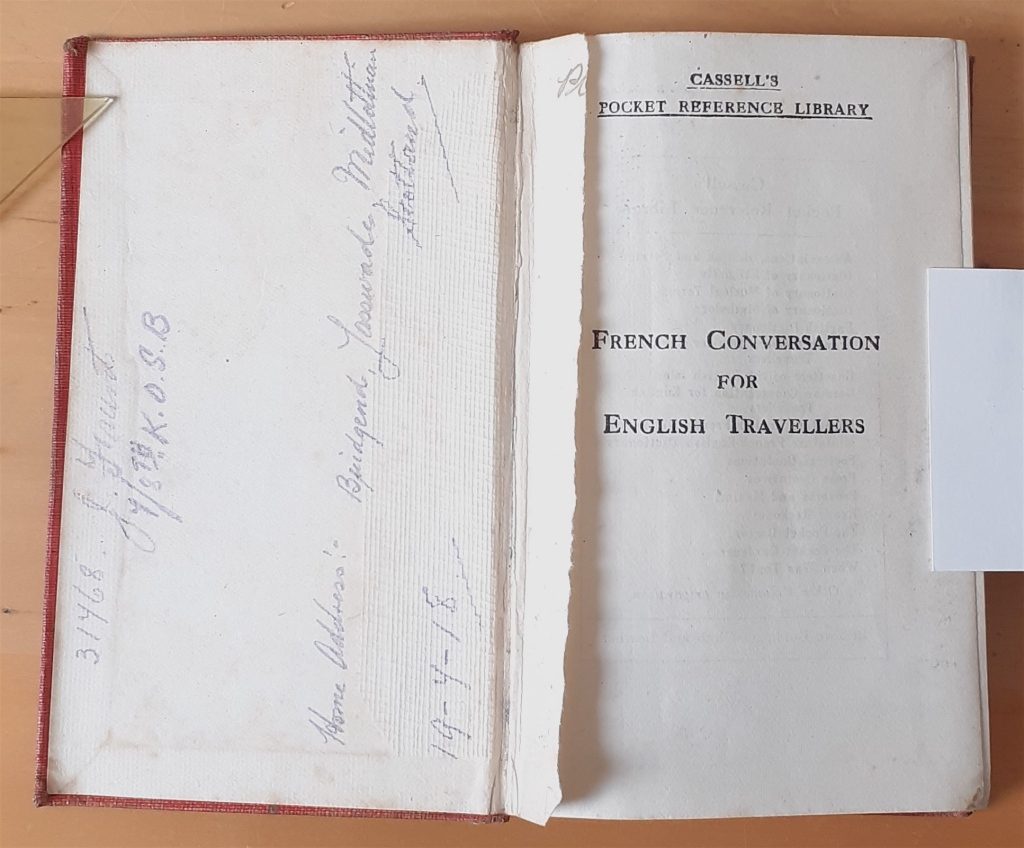

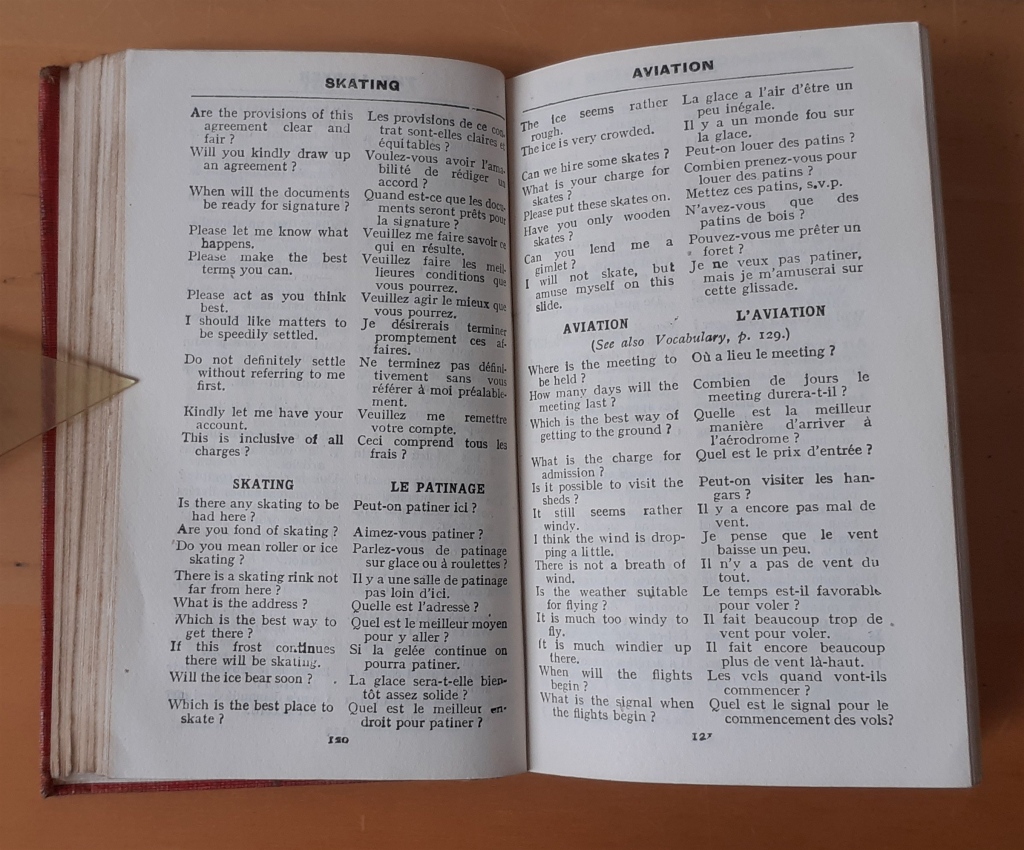

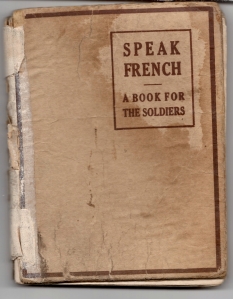

As this project enters its second decade, and has shown how important and fruitful it has been to move beyond the iconic dates and the trenches of the Western Front, we extend both an invitation and a challenge with the next set of questions, knowing there are many more. What was the linguistic experience of South-East Asians in France, Annanites and the Thai forces contingent (which arrived late in 1918)? How useful were phrasebooks to the Chinese Labour Corps? Did foreign language theatre productions in the UK and elsewhere actually help people feel a connection to their allies? How was the communication between Britain and France and the Japanese fleet in the Mediterranean managed? Did the German army attempt to manage tension between regional regiments through acceptance of differences of dialect? How did the Russian army manage differences of language? What was the management of communication between the German and Austro-Hungarian military and the Turkish military?

Certainly, there is scope for another volume of essays to take the subject area further. Rather than take the ‘wait and see’ advice of Herbert Asquith (Britain’s Prime Minister till 1916), we invite suggestions.

Many thanks to Hillary Briffa for onsite management of the connections across multiple continents and time zones, to Julian Walker and Christophe Declerq for their ongoing leadership of this project, and to King’s College London for hosting the event.