There have been many comments recently on social media on the inappropriateness of using war metaphors in the management of the pandemic. Should health-workers be described as ‘frontline workers’, should those who contract Coronavirus be described as ‘fighting’ the disease, should they ‘win’ or ‘lose’ their ‘battle with the disease’. Is the virus ‘the enemy’? In purely health terms such comments are seen as misleading, as no conscious struggle is involved; the danger is that they imply that those who die are seen as failing, and at worst, wasting the depleted resources. Their treatment is implicitly a waste of money as they did not try harder – thus they fail twice, failing to beat the disease and failing the national effort.

The Queen, with a clear and direct connection to the Second World War, in April 2020 referred to her first broadcast, in 1940, and to possibly the most well-known song associated with that conflict. Discussions of whether it makes for an easy model for helping the mind digest what is happening, or whether it is cheap and lazy thinking will go on, and there are pros and cons; what is undeniable is that the crisis has, just as in 1914, been taken up by commercial advertising.

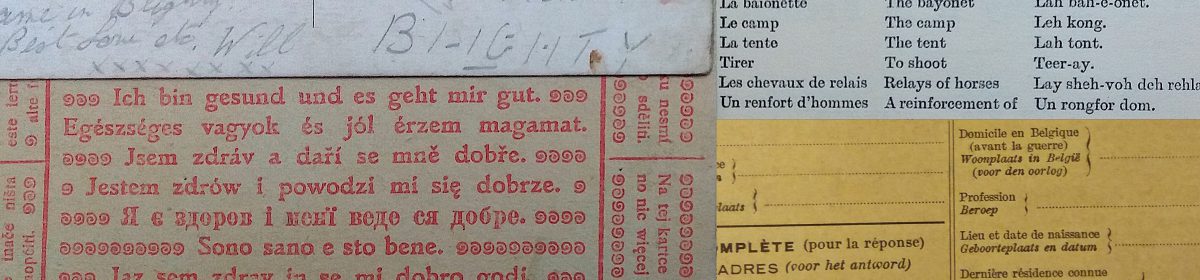

Within a couple of weeks of the outbreak of the First World War commercial marketing writers were using war terminology to help sell their products, ranging from the fairly drole ‘Business as Usual, during European alterations’ in TheBoot and Shoe Retailer,September 1914,to ‘It’s along way to Tipperary but it doesn’t seem a long way if you are wearing Wood-Milne rubber heels and tips’ in the Daily Sketch, December 1914. Some of these can be perhaps excused, as they were advertisements for products such as cigarettes, toffee, or shaving soap, which were of direct use by soldiers. There were even advertisements that made puns on the Somme/some, as in February 1917 The Tatler carried an advertisement for Gibbs’ shaving soap with the headline: ‘“Somme” shave – It is really “some” soap, this Gibbs’s.’ Commercial companies sponsored food parcels and phrasebooks for soldiers, making sure their names were associated to the product. Was this support or exploitation, or did it uncomfortably embrace both?

As then so now; television advertisements run sequences indicating support for the NHS, with company tags at the end. The companies are in some cases running charitable campaigns, supplying food to the needy, or they may be just encouraging viewers to follow government guidelines. Again the moral ground has hazy edges: health-workers need to relax, and surely many would benefit from the products of a major multinational communications company; many people are going hungry and will undoubtedly benefit from the charitable distribution of food by a major supermarket chain; much extra revenue will accrue from customers who will feel that in buying the products of these companies they are supporting the companies’ support. The end recipients of the revenue will include health services, those who benefit from the charities, and the bank balances of the companies involved.

The language of war in 1914-18 was used for commercial gain; the new ‘front line workers’ are being used in the same way now. At the same time charities benefit and campaigns to overcome the virus succeed. Government public information campaigns sit in the same space as commercial advertising; they use the language of commerce. Capital-based economics will always see more commercial potential in being part of the treatment rather than prevention; just as in 1914, money is the language of war.